On control, uncertainty, and choosing art anyway.

When I made the decision to shut down Bitmark early this year, it felt like watching a decade of my life vanish into the void. I had spent years and millions of dollars trying to give people real ownership in the digital world, and when it collapsed, I couldn’t make sense of it.

I failed to raise another round. I failed to keep the team together. I failed to convince investors that digital art was worth fighting for. But I couldn’t convince myself to stop believing in it either.

The hardest part wasn’t the loss. It was the conviction that, somehow, this was still worth it. Even as I stared at the numbers, watched our savings shrink, and fought to pull Feral File out of Bitmark’s wreckage, I couldn’t walk away. Against every rational instinct, I decided to pour what little I had left (time, money, belief) into art.

That decision terrified me.

I studied math and physics. My whole career had been about control: taking messy, unpredictable systems and making them behave. So why was I choosing something that refused to behave? Why art?

I went back to the beginning, to the origins of the computer itself, searching for a thread that could make sense of it all. I wanted a reason, something rational that could justify what felt like an irrational leap.

That’s when I reread Alan Turing’s 1936 paper on computability. What I expected to be pure math, a cold proof about symbolic machines, read instead like an artistic manifesto.

Turing described a machine that could simulate any process describable in logic. A machine of pure abstraction. The idea was so radical that even now it’s hard to feel the ground beneath it. His “universal machine” wasn’t just a theory of computation; it was a metaphor for everything that could ever be imagined or built.

Reading that, something cracked open in me. I began to see how artists, scientists, and engineers of that era were circling the same mystery from different sides. They weren’t simply creating tools; they were building a new kind of mirror for consciousness itself.

The awakening of form.

In the early twentieth century, both art and mathematics were going through revolutions. Mathematicians like Hilbert were searching for perfect logical foundations; artists like Malevich and Mondrian were stripping reality down to grids and fields of color. Both groups were chasing purity in an attempt to express essence through structure.

Turing’s proof landed right in the middle of that search. Suddenly, there was a system that could contain all other systems. A finite set of symbols could give rise to infinite expression. That sounds technical, but it’s also deeply spiritual.

When I first grasped this, I thought: this is art disguised as math. It’s the same impulse that drives an artist to create rules and then watch what life grows inside them.

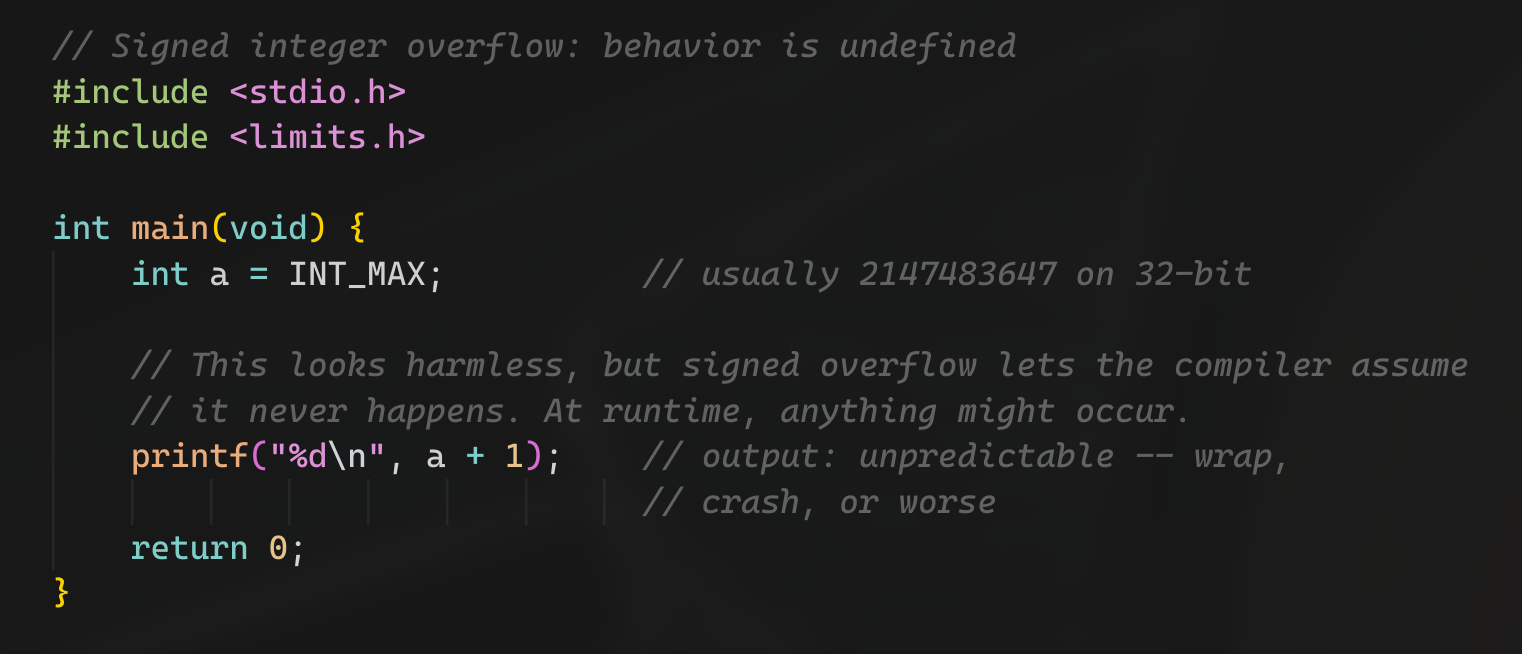

I thought of my early years in Taiwan, working on operating systems for phones so underpowered they seemed allergic to abstraction. We wrote C by hand and feared every stray instruction. That’s where I met undefined behavior: the moment your program compiles cleanly but reality rewrites itself underneath.

The first time I watched that happen, it felt cosmic. I had spent years building systems that were supposed to behave, to prove that control was possible. But in that moment, I saw how easily precision could collapse into unpredictability. It wasn’t failure; it was revelation.

I’m still wired to want control. That impulse runs deep; it’s what makes me a builder. But ever since that moment, I’ve carried a quiet unease. If a perfectly written program can still turn against its author, then maybe creation isn’t about mastery at all. Maybe it’s about living with the tension between structure and surprise. The same tension that makes art feel alive.

From computation to composition.

The first artists to touch computers, people like Vera Molnár, Frieder Nake, and Harold Cohen understood this intuitively. They weren’t interested in speed or efficiency. They were interested in conversation. They wrote algorithms the way a composer writes scores: instructions that would produce variations, deviations, even contradictions.

Molnár would add random perturbations to her geometric drawings so each run was unique. Cohen spent decades training AARON, a program that could generate drawings without direct human control. These were not tools; they were collaborators. The machine wasn’t a brush; it was a co-author.

My friend and business partner Casey Reas once took me to an exhibition of Molnár’s work a few years ago. I had seen images online, but standing in front of those prints felt different. The lines carried both precision and hesitation, as if the plotter itself had paused to think. I left the show feeling disoriented, like I’d glimpsed a kind of authorship that didn’t need to belong entirely to a person.

Later, while trying to understand how artists today were working with AI, I stumbled onto Harold Cohen’s AARON. Watching its slow, deliberate drawings appear on the screen reminded me of the systems I had built that sometimes seemed to think for themselves.

Once, while testing a scheduling algorithm for a distributed network, a minor timing bug sent the system into what looked like a loop. I was ready to kill the process when I noticed a strange pattern forming in the logs: a rhythm of failure and recovery, an emergent pulse. It wasn’t what I’d intended, but it wasn’t random either. It had its own logic. One that existed somewhere between order and error.

Moments like that make me uneasy and exhilarated at the same time. They’re reminders that every system contains the potential to surprise its author. Control and curiosity are always wrestling for dominance, and maybe that struggle is the point. The first computer artists weren’t trying to escape that tension; they were trying to compose with it.

The modern recursion.

Fast-forward to today’s AI. We’ve built models that no longer just follow rules; they learn them. They generate images, music, and text we can’t fully explain. The same question that haunted the 1960s now echoes louder: if a machine can create, who (or what?) is the artist?

I’ll never forget seeing Casey’s Compressed Cinema on a seventy-foot screen. Entire films reduced to flickering memories. Frames dissolving into something halfway between motion and thought. Sitting there, I felt the floor of authorship tilt. It was as if the machine were dreaming the history of cinema back to us.

That experience made me look back at Mario Klingemann’s work with new eyes. His neural-network portraits were raw, uncanny, and years ahead of their time, experiments in machine perception before most of us were even asking the right questions. Both he and Casey were exploring different edges of the same frontier: what it means to collaborate with systems that invent alongside us.

And then there was Sofia Crespo. We were in Dubai together for a conference, an unlikely gathering of technologists, artists, and policymakers. Between panels she opened her laptop and showed me early images from Neural Zoo. Hybrid creatures, translucent and precise, breathing with data instead of air. I remember thinking they looked like life trying to remember itself.

These moments left me with a feeling I still can’t quite name. It wasn’t pride or fear or envy. It was recognition. I realized I was watching a new form of creativity unfold around me, one that blurred the line between human intention and machine intuition.

Their work has never been about replacing human creativity. It’s about extending perception, testing how far consciousness can stretch through computation. And that feels astonishingly close to what Turing was reaching for when he speculated about “intelligent machinery.” He didn’t just foresee artificial intelligence; he glimpsed artificial imagination.

What I think I’m really doing.

When I reread those papers now, twenty-five years older, I don’t see computer science. I see a philosophy of making. One that connects logic, art, and human longing. The computer, in Turing’s sense, isn’t just a tool for calculation; it’s a stage for possibility. It’s the first medium that can hold all other media, including thought itself.

And maybe that’s why I couldn’t let go after Bitmark. Ownership, property, autonomy, those still matter to me, but they feel incomplete without that deeper kind of feeling, the one that unsettles and expands you at the same time. Art asks different questions. It measures progress not by efficiency or output but by feeling.

If my mission has always been to build better foundations for human exploration, then art isn’t a detour. It’s the foundation itself. It’s how we test the boundaries of consciousness.

I can’t justify it in a spreadsheet. But I feel deeply that art and technology are not separate pursuits. They are two halves of the same attempt to understand what we are capable of imagining. And lately I keep asking: what happens when we let machines feel with us?

That question keeps me up at night. Because the more I build, the more I realize that creation and control pull in opposite directions. Every system, technical or personal, carries its own uncertainty.

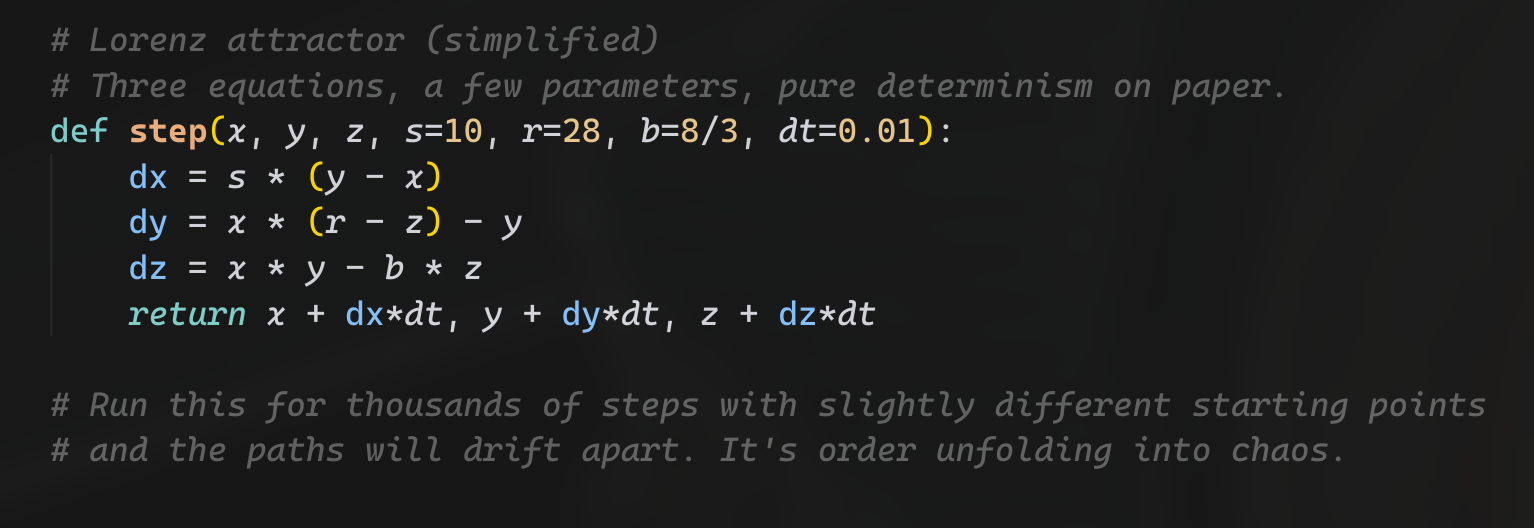

I think of the Lorenz attractor: three simple equations describing air currents. Perfectly deterministic, yet impossible to predict.

Change one bit in the starting value and the pattern diverges forever. I once tried to reproduce it across two machines and watched them drift apart within seconds, spiraling into different galaxies of motion.

The math was flawless; the outcome was chaos. If I can write the equations and still not foresee the result, what does that say about understanding itself?

It reminds me that even with perfect rules, control is an illusion. Maybe that’s the same lesson art keeps teaching us in softer ways: that freedom lives inside the very limits we set.

The infinite simulator, again.

Every time I watch code generate an image that has never existed before, I think about Turing’s thought experiment: a simple tape, a reader, a set of rules, and infinite outcomes.

He proved that a finite system could simulate the infinite. Artists have been proving the inverse ever since: that the infinite can live inside us too.

Maybe that’s the real dialogue I’m trying to join. Maybe this whole journey, from math and physics to hardware to art, has been one long attempt to reconcile those two directions of the same machine, the one that runs in silicon and the one that runs in consciousness.

If I can keep building bridges between them, creating machines that let more people feel that connection, then maybe this irrational obsession finally makes sense.

Distributed via Edges.